Scenario planning is a disciplined way to formulate strategic hypotheses in the context of existing driving forces and their uncertainties.

Any strategy is based on hypotheses and scenarios. What value does scenario planning add to strategic planning?

With scenario planning, we are trying to get a broader picture of the hypotheses by extrapolating the existing driving forces and creating plausible scenarios.

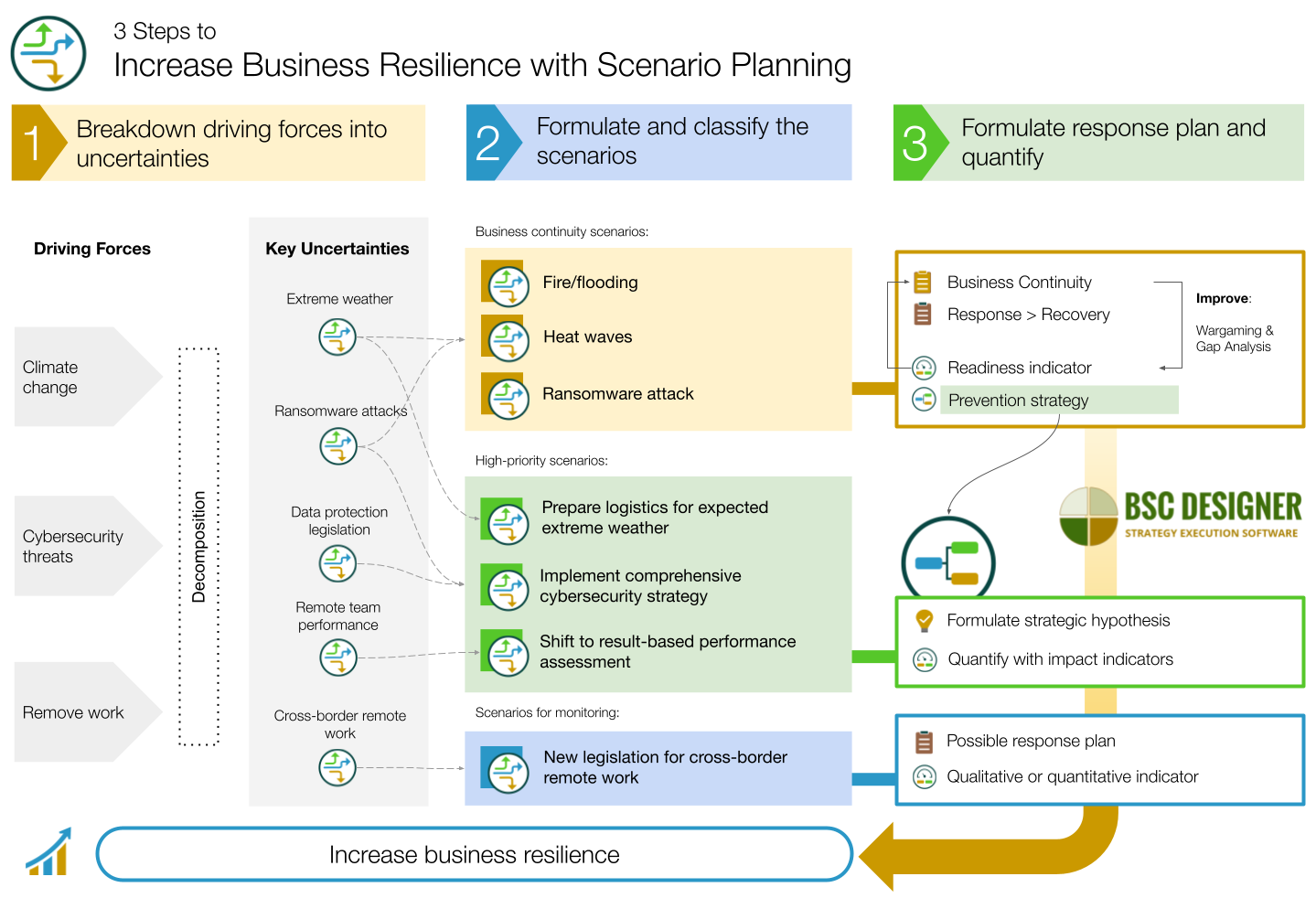

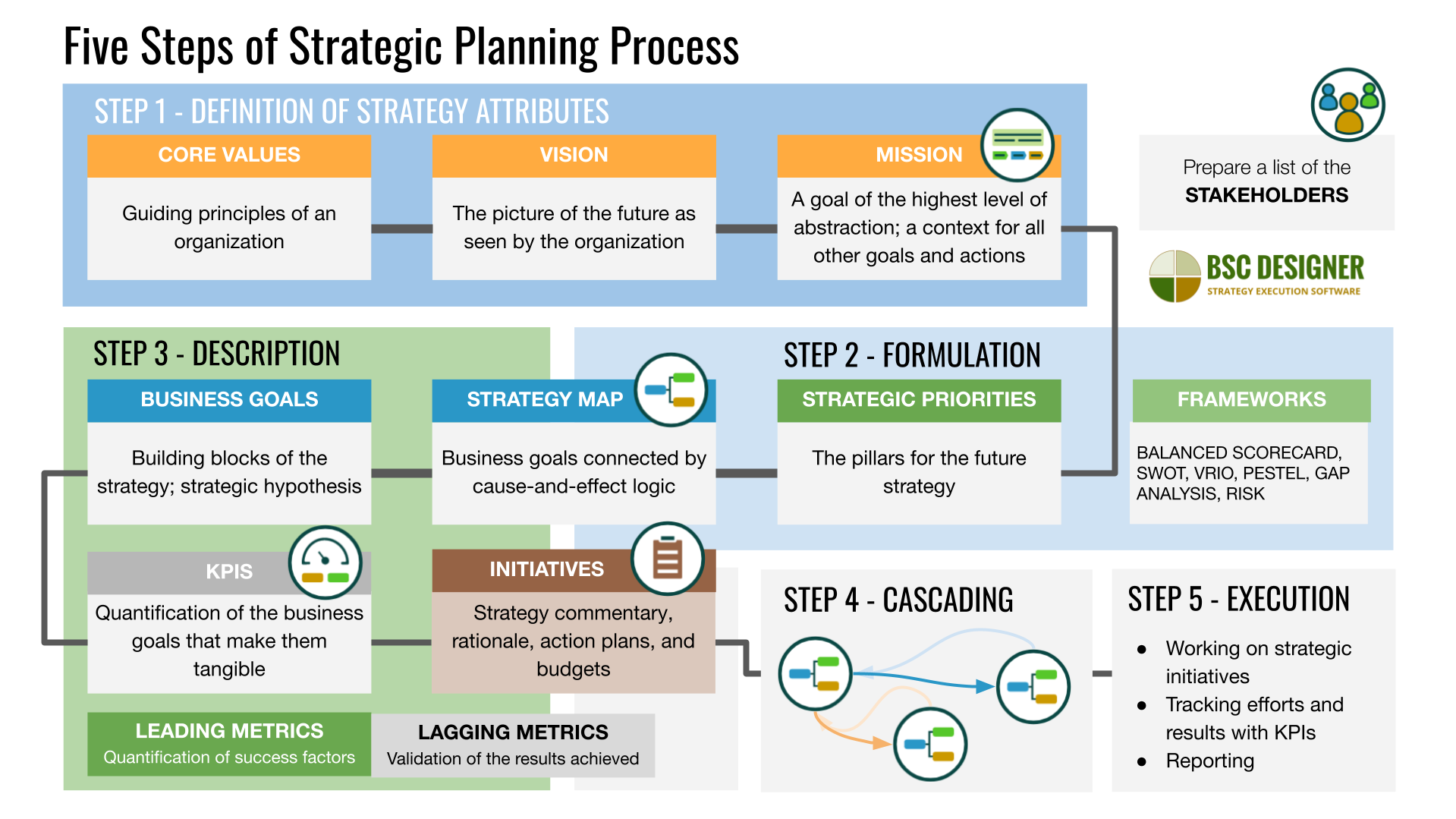

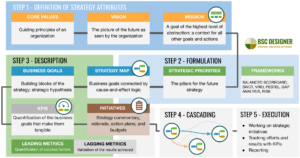

From the viewpoint of the strategic planning process, scenario planning can be used in the strategy formulation step 1 (step 2) together with other frameworks that help generate strategic hypotheses.

The same broad picture of hypotheses helps to understand the risk landscape better. Diverse scenarios and simulations via wargaming 2 help to create more detailed risk models and risk mitigation plans.

In addition to the obvious strategy analysis function, properly implemented scenario planning with early sign indicators, prevention, and response plans starts playing the role of a strategy description tool. This is reflected in the position of scenario planning in the frameworks ecosystem diagram.

By definition, scenarios are about plausible future states related to the expected business trajectory of the organization. In this sense, scenario planning belongs to the segments of decomposition by time perspective and decomposition by cause-and-effect logic.

Have a look at the PESTEL analysis article published right before Covid-19 became a pandemic. Some of the mentioned trends were:

There was no “Covid-19” mentioned (although at that time, there were some serious warnings coming from Asian countries). Still, with those general trends in mind, any organization could start scenario planning by asking a number of “what if…?” questions:

With scenario planning based on the findings of PESTEL analysis, it looks like we could have scenarios for around 30% of the challenges that we faced during the pandemic and afterwards.

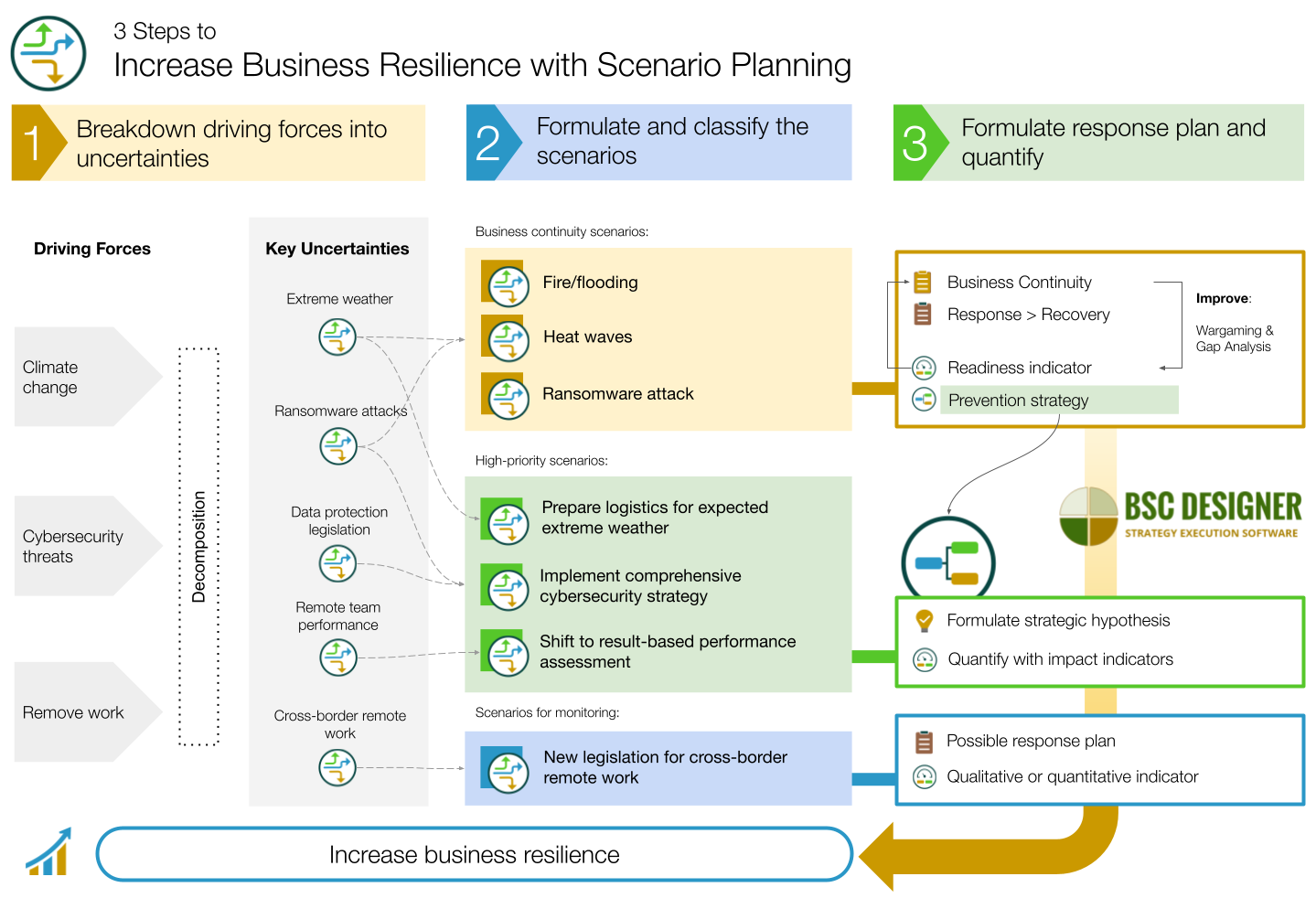

Here is a three-step approach to scenario planning by the BSC Designer team:

Identify the driving forces for your organization by using:

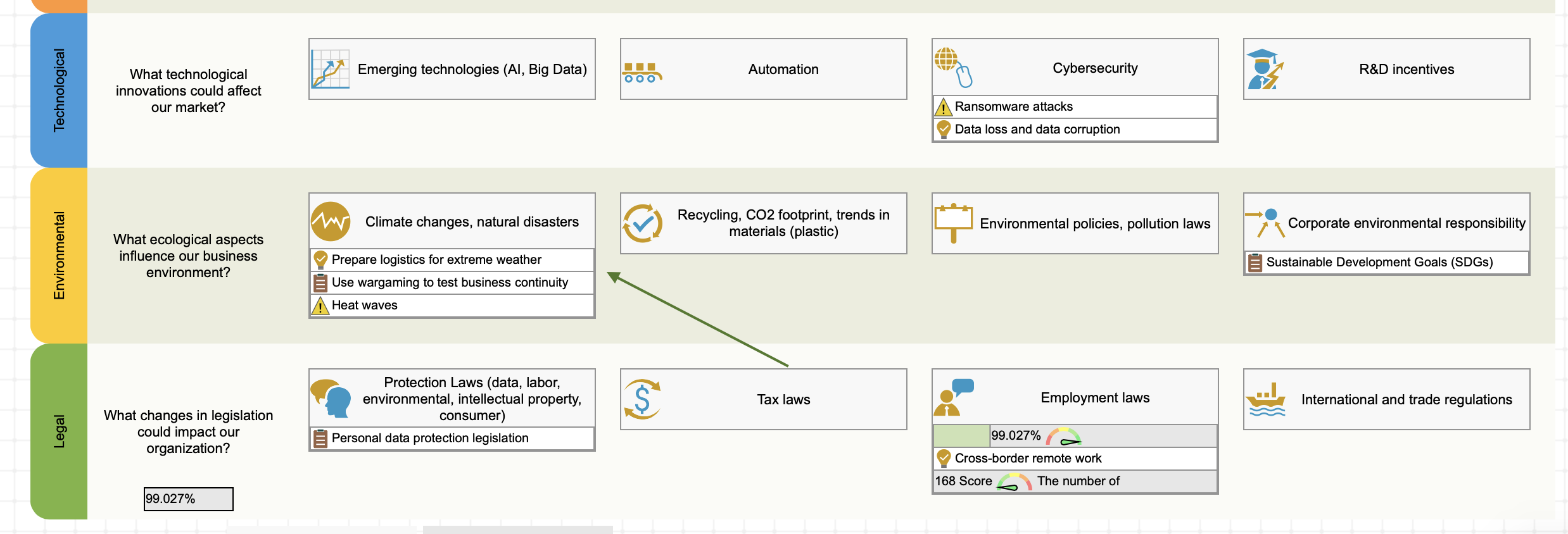

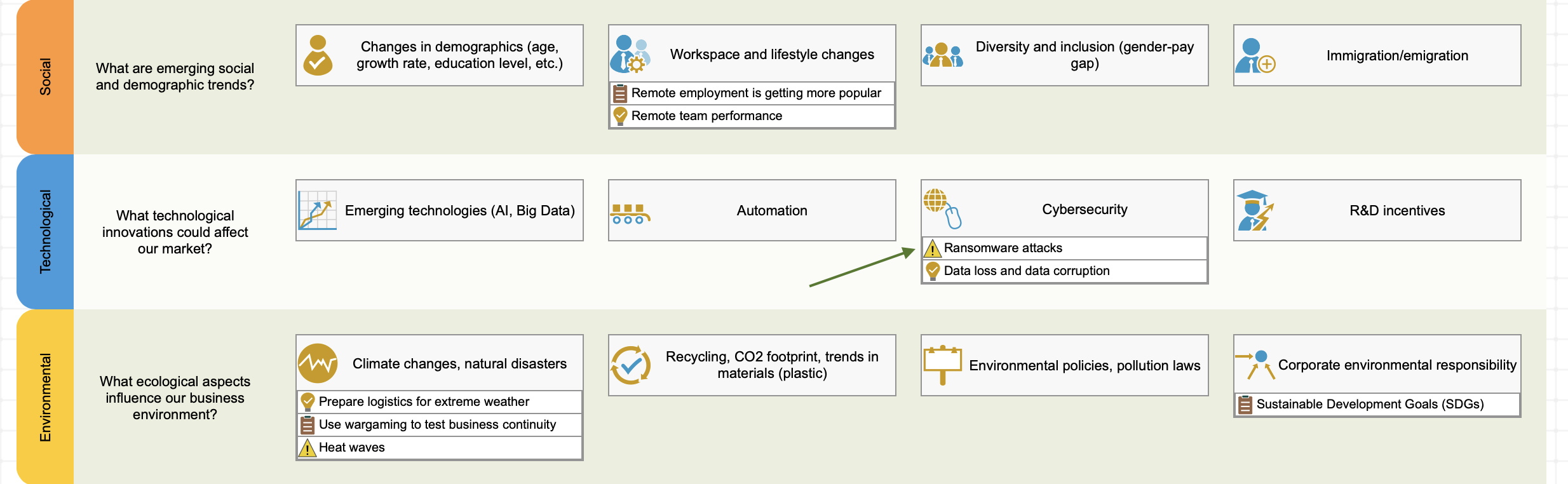

The global driving forces need to be broken down into more specific uncertainties relevant for your organization. Let’s use our PESTEL template to practice it with some driving forces.

In the latest IPCC’s Assessment Report 3 , several climate change scenarios were presented. In essence, the report discusses different warming scenarios depending on the decarbonisation efforts.

Two initiatives and one risk factor ('Heat waves') aligned with the driving force 'Climate change'.

The mentioned scenarios will have a direct impact on the energy industry. For other industries, a complex idea of climate change needs to be decomposed into specific consequences relevant to specific regions and business environments.

A starting point would be to look at the Global Change Research Program or the web of European Commission, where some specific consequences of climate change are outlined:

Beyond the obvious impact on agriculture, climate change will affect:

With these ideas in mind, instead of focusing on climate change in general, your team can focus on a few uncertainties that are most relevant for your region or industry.

The Sendai Framework for Disaster Risk Reduction 4 was adopted by 187 countries. Designed for national governments and local authorities, it also stresses the need to incentive businesses to invest in risk reduction and business continuity planning.

The adoption of the Sendai Framework by city or regional authorities includes risk assessment (see Priority 1: “Understanding Disaster Risk”). Organizations can update their risk models to incorporate the risks addressed by the local implementation of the Sendai Framework.

The Sendai Framework encourages authorities to incentivise sectors of business to align their scenario planning with resilience building (see Priority 2: “Strengthening Disaster Risk Governance to Manage Disaster Risk”).

The alignment can be affected:

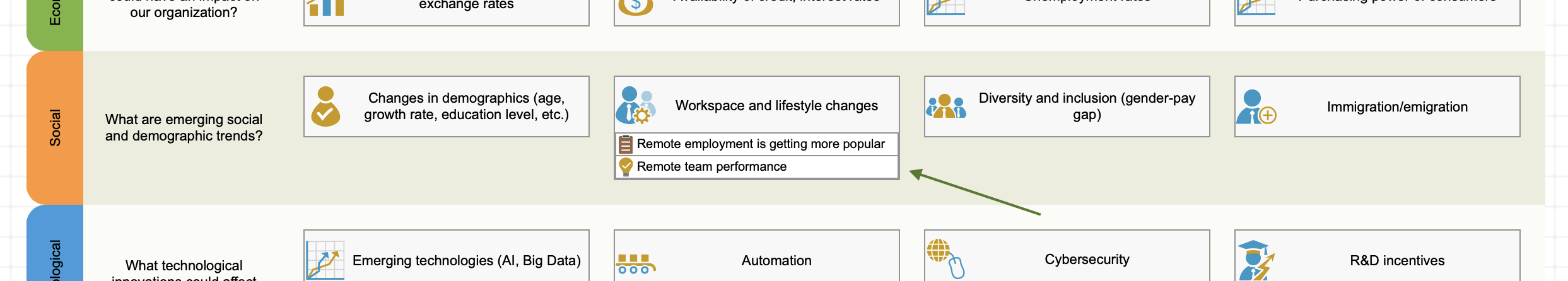

Remote work is here to stay 5 . In 2021, we saw that:

A broad driving force 'Remote employment' is aligned with driving force 'Workspace and lifestyle changes'.

What are the future challenges of remote work? According to the KPMG report 6 , one of the emerging trends is the cross-border remote working arrangements.

Is this uncertainty relevant for your organization? In our case (we are a team of remote specialists), the broad driving force “remote work” can be projected into a specific uncertainty of “cross-border remote work.”

Cybersecurity is another emerging trend. How can we break down this broad driving force into something more specific?

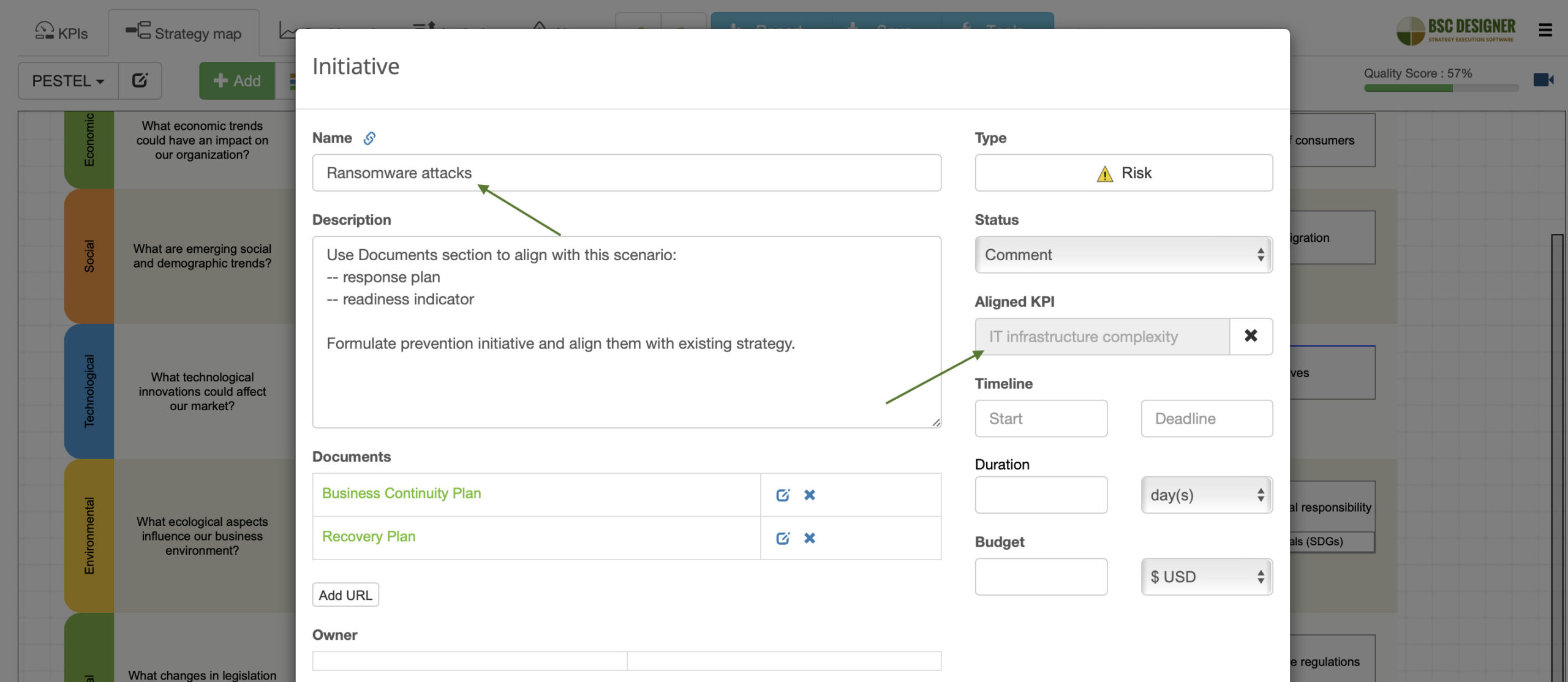

The threat 'Ransomware attacks' is aligned with the 'Cybersecurity' driving force detected by PESTEL analysis.

Here are the typical cybersecurity threats we discussed in the previous article:

Depending on the data flows in your organization and underlying IT infrastructure, you can pick a few relevant uncertainties. For example, a ransomware threat looks relevant for any organization.

Ransomware is still a very broad uncertainty. For example, its more specific projection could be the uncertainty associated with cloud deployments being the target 7 of ransomware attacks.

Once the general threats are projected into uncertainties, we need to better formulate the scenarios and agree on how to manage them.

Shell was one of the pioneers in the large-scale application of scenario planning for business. There are many things we can learn from them, and probably the most important one is that possible scenarios formulated as stories work better. Those scenarios are easier to explain and immediately capture the attention of your team.

Besides formulating basic scenario as:

Ransomware attack on our cloud deployment

think about the story that stands behind this scenario:

“One day, you are trying to login into your online account, and it returns a strange error… Your customers start sending you reports about problems with the service. You are on the phone with IT specialists, but they say that it looks like they don’t have access to … ”

Scenarios in the form of stories are much easier to “sell” to the key stakeholders.

Scenarios vary in their urgency and probability. We classify scenarios into three categories:

Scenarios related to business continuity.

High-priority scenarios that resonate with existing strategy and can be implemented right now as a new strategic hypothesis.

Scenarios for monitoring – important scenarios, but without clear alignment with current strategy.

One scenario might fit all three categories. For example, ransomware attack:

Different types of scenarios require different ways to formulate response plans and quantify them. Below, you will find our suggestions for:

Disaster recovery or business continuity planning focuses on scenarios that might affect critical functions of the organization. The potential threats, in this case, are rapidly developing natural disasters, cyberattacks, resource outages, etc.

We explored business continuity management in detail in another article. Below, I share some general ideas.

Business continuity planning starts with business impact analysis. In simple words, we need to identify disruptions that could possibly affect our organization, identify the key operations affected by those threats, as well as critical recovery time.

The specific threats, in this case, depend on the nature of your business. A common starting point are:

Your team can quantify the threats according to their:

Once the threat is described, we need to define several plans:

We are now prepared for a case of a risk event occurring. Additionally, we can discuss how to prevent such events or minimize their impact.

Compared to other types of scenarios, the business continuity scenarios typically occur immediately or with a short early warning period. While there are no specific early sign indicators, there are certainly some leading factors that predict the readiness of your organization for a scenario.

The risk of ransomware attacks is quantified by the 'IT infrastructure complexity' metric; additional details can be explained in the aligned 'Business continuity plan' and 'Recovery plan'.

For example, we discussed some of the leading indicators in the article about cybersecurity:

By quantifying these leading factors, we can define the readiness indicator for the business continuity scenario.

Additionally, we can quantify recovery plans with some lagging indicators. For example, for a cybersecurity attack, we can track:

These metrics will help your team to better prioritize their efforts.

Compared to other types of scenarios, business continuity scenarios involve fewer uncertainties. The nature of such scenarios is better studied. For example, we might not know where and when the next hurricane will hit, but we know what a hurricane is, what kind of damages are expected, and what we can do to minimize damages.

The business continuity plan can be tested via simulations of the scenarios or wargaming, where the rules of the “game,” as well as expected outcomes, are defined.

For example, what if your company becomes a victim of a ransomware attack? What data can be effectively restored from a backup? Run the simulation of attack to find the gaps and improve weak points.

After testing the scenarios, we will have additional data for the readiness indicator.

You can find more specific examples for managing business continuity scenarios in the article dedicated to the topic.

High-priority scenarios don’t have such a dramatic impact on critical business operations like business continuity scenarios, but they might significantly affect the execution of existing strategy.

Our goal is to align a high-priority scenario with existing strategy. To do this, we convert scenarios into a strategic hypothesis.

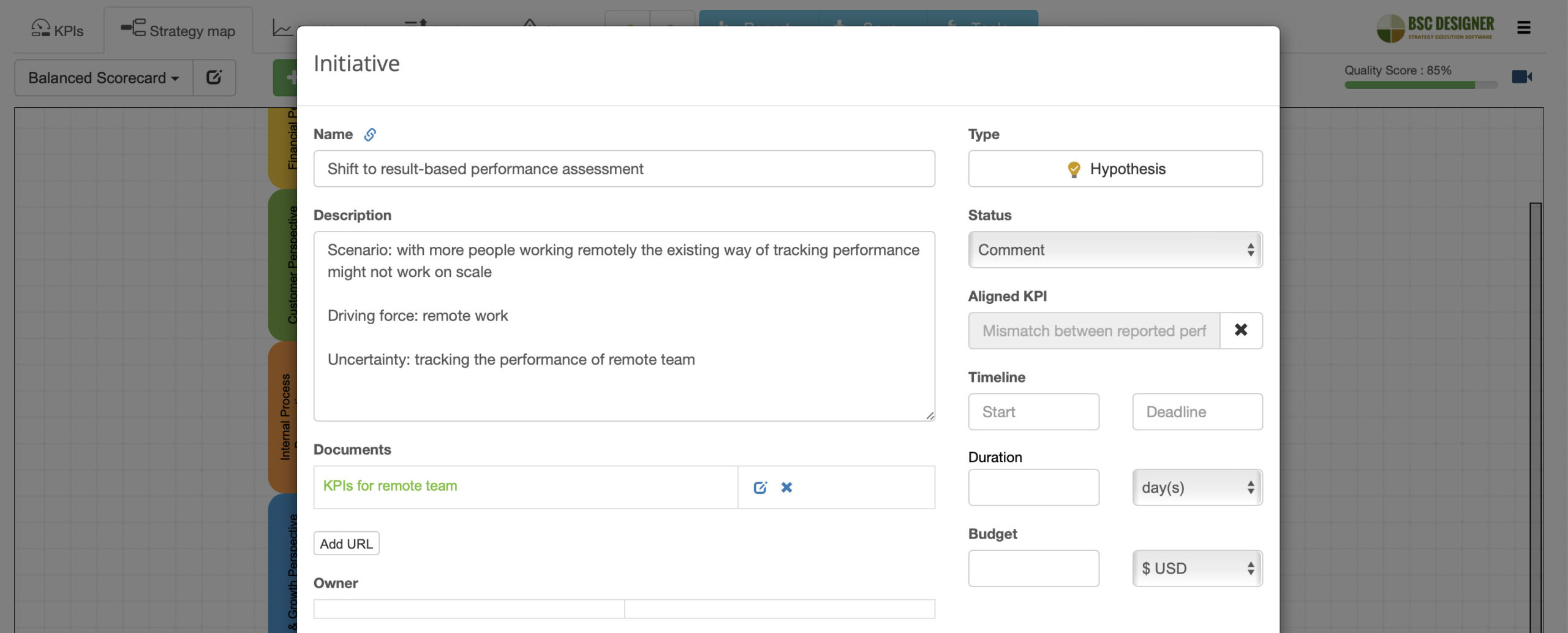

For example, one of the actionable aspects of remote work driving force is the need to access the performance of the remotely working team because the existing ways to track the performance might not work well on scale.

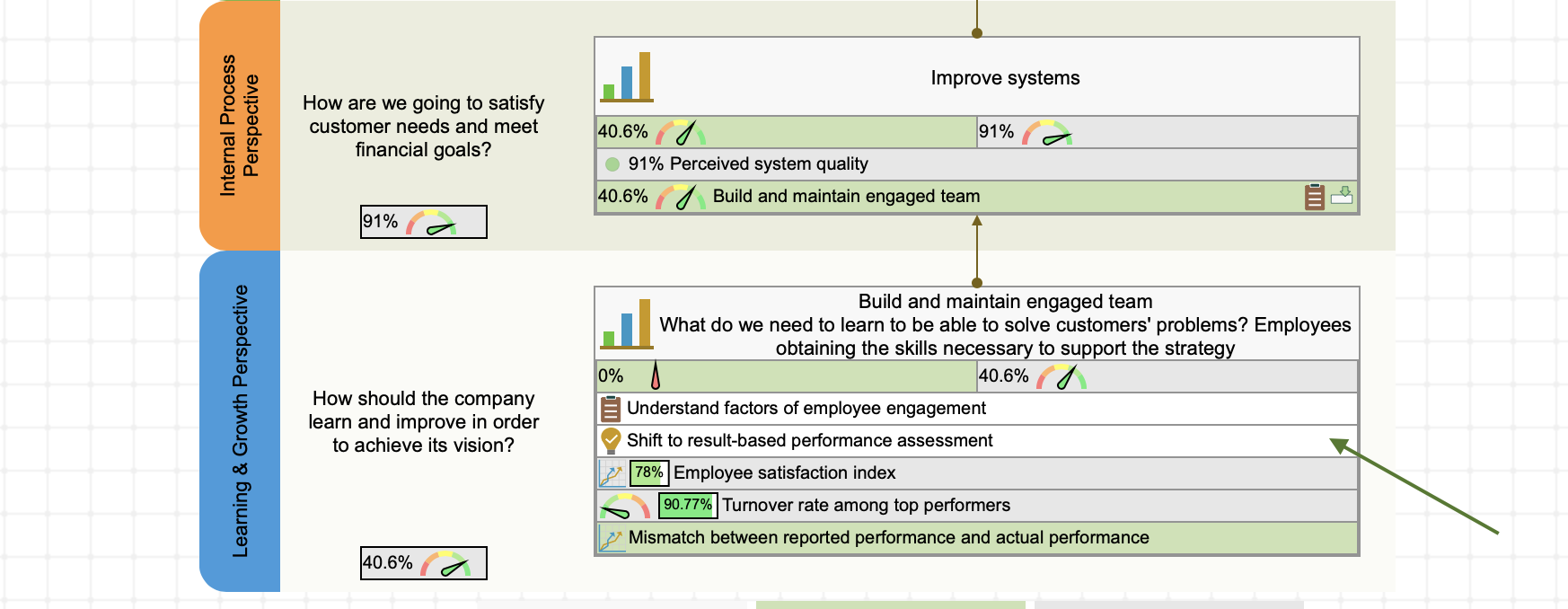

Let’s use the CEO scorecard template available in BSC Designer to illustrate the alignment steps. In the Learning Perspective, there is a goal formulated as Build and maintain an engaged team.

The shift to result-based performance assessment is a good hypothesis to test for this goal.

The hypothesis 'Shift to result-based performance assessment' is formulated for the 'Build and maintain engaged team'.

Typically, the high-priority scenarios already have some kind of impact on business performance. In our example, we can quantify the existing impact of the remote work scenario with these indicators;

Plausible scenario, driving force and uncertainty in the description field of the hypothesis.

Additionally, we can find some process-related indicators. For example:

The Cross-border remote work scenario that we discussed above sounds like something that we can see in the near future. We can map it in a separate scorecard with plausible scenarios.

To define the possible way the scenario will be developed, we can speculate on the worst/best cases of developing an uncertainty and put it on scale. For example:

In this example, the legal landscape can be changed, so we formulate response plans for this scenario:

In contrast to high-priority scenarios, most likely, we won’t find the impact indicators, as there is no impact yet. We can speculate about the possible impact, but it might be too early.

In this case, we can track the qualitative or quantitative early sign indicator. For example, we can look at the projects for new legislation that addresses specifically cross-border remote working.

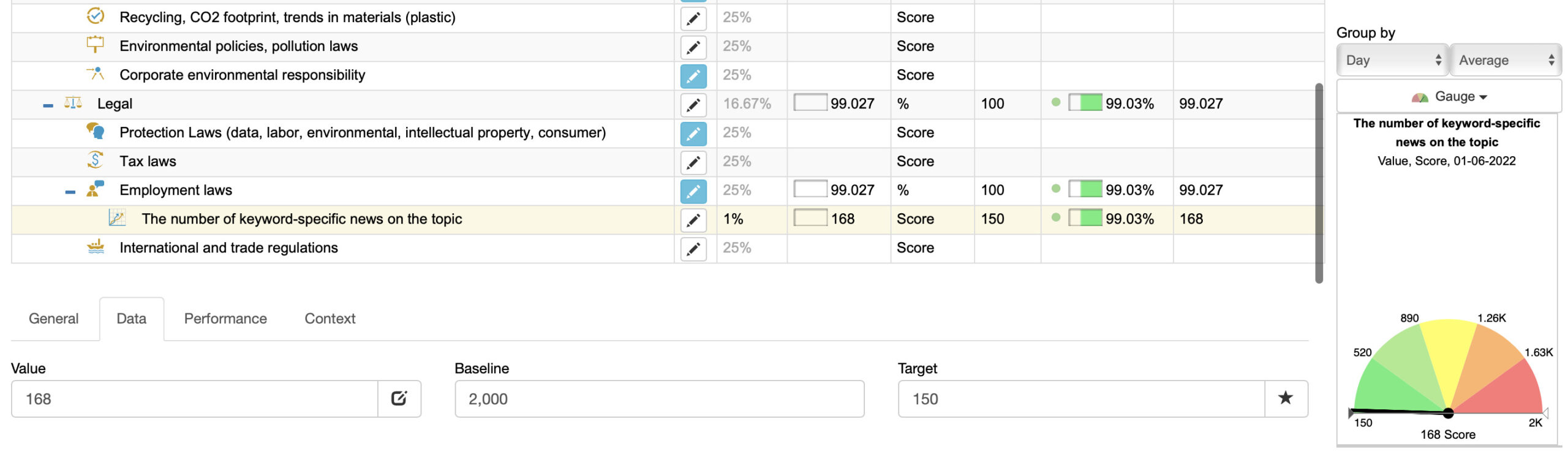

An example of the early sign indicator ('The number of keyword-specific news on the topic') aligned with the 'Employment laws' trend.

Quantifying the existence and the progress of such projects directly might be time-consuming, so instead, we can find a proxy metric. Typically, the new legislation is widely announced and discussed in the press. We can quantify the number of publications with certain keywords. For example, if I search Google for “cross border remote work,” now I get just 63 results in the News section and 4460 results in classical search. There are some publications by reputable sources like PWC that confirm that the trend exists, but still, there is no sign of specific legislation coming soon.

We can use The number of keyword-specific news on the topic as an early sign indicator for the scenario. This indicator is not bias-free, but it gives us a good estimation.

What should we do with a scenario when an early sign indicator shows that things have started changing?

Depending on the scale of changes, we have two options:

Another possibility is that with time, the scenarios lose their relevance. For example, with transition to sustainable energy and distributed energy production, some energy-related scenarios will no longer make sense. In this case, we stop monitoring and archive them.

We started with a promise that scenario planning increases business resilience. A logical question would be:

What is our current level of business resilience?

Quantifying resilience, in general, doesn’t make sense. If we do so, we will find out how resilient organization is to the past challenges.

Talking about resilience, we are interested in understanding the readiness of the organization for the future challenges. We can make a reasonable assumption:

Having a diverse picture of the existing driving forces and investing time in discussing scenarios based on those driving forces increases the organization’s resilience

Give scenario planning a try! Reformulating a known saying… the best time to start scenario analysis was a few years ago, then the second-best time is now.

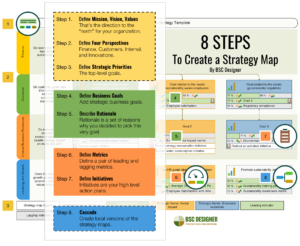

Strategic Planning Process:

Examples of the Balanced Scorecard:

Strategy Maps:

Alexis is the CEO of BSC Designer with over 20 years of experience in strategic planning. He has a formal education in applied mathematics and computer science. Alexis is the author of the “5 Step Strategy Deployment System”, the book “10 Step KPI System”, and “Your Guide to Balanced Scorecard”. He is a regular speaker at industry conferences and has written over 100 articles on strategy and performance measurement. His work is often cited in academic research and by industry professionals.